1954 HUCKINS

HORSEPOWER

LENGTH (FEET)

YEAR COMPLETED

BUILD TIME (MONTHS)

Northern Spy

A 1950’S BOAT WITH 21ST CENTURY POWER

It’s no small task to repower a wooden Huckins with Volvo’s IPS propulsion – here’s how it’s being done.

If ever there was a great boat tale involving a blend of old and new technologies, this has got to be it. Take one classic 1954 Huckins motoryacht built of two layers of 3/8-inch mahogany planking laid out diagonally, screwed to oak framing and fiberglass-sheathed on the outside.

Add Volvo’s IPS pod drive propulsion, the modern, efficient, maneuverable planing-hull propulsion system. Shake, stir, whittle and chisel – and out comes a much better boat than the original. That is this project – and its rationale – in a nutshell.

This is a great story on a number of levels. The left-brain skeptic asks who would want to take a 56-year-old wooden boat and put a pair of IPS drives in it? I asked myself the same question and it is quite easily and convincingly answered: 1) It’s never been done before; 2) the boat is built of wood, and restoring the hull structurally and integrating the IPS drives takes more skill, deliberation and intelligence to do well than a fiberglass hull would; 3) a difficult job done well is its own reward; 4) the boat has a pedigree and a history that make it worth restoring; 5) it looks nothing whatsoever like anything else out there (except another Huckins) – a definite up-check when considering the bloated me-too tubs populating marinas today; 6) it has a wonderfully accommodating layout that uses space efficiently and smartly; 7) the interior is flooded with natural light through many large windows; and 8) there is no hint of the lamentable trend to cram just one more couch or icemaker or cedar-veneered locker into every cubic foot of interior space.

And with a yard that has the talent and technology to pull off the job, why not? After all, this boat will be good for at least another 50 years when these guys have finished their work, assuming she’s well taken care of.

Let’s roll back the tape a few years. The Huckins was in Florida when the previous owner bought it in 2005. It was in rough shape, so the owner took it to the Huckins yard in Jacksonville for restoration (www.huckinsyacht.com). Though Huckins builds fiberglass boats today, it still has wooden-boat craftsmen capable of restoring its classics. Bill Morong, the head of Yachting Solutions, the Rockport, Maine-based primary contractor on this project, was hired as project manager. With only eight boats to manage back in Rockport at the time, he was able to spend six months at Huckins overseeing the work.

And that work was extensive, with 80 percent of the keel, garboard and broad strakes (the two planks abutting the keel), along with the lower portions of all frames, replaced. Sheathing a wooden boat with fiberglass adds strength, as well as abrasion and impact resistance, but it also hides whatever’s happening in the wood substrate. This made the restoration more challenging, with surprises cropping up as things went along. New castings were made to duplicate the original Huckins bronze and aluminum deck hardware, restoring the boat to something very close to its original appearance.

With the exterior overhaul complete, Morong brought the boat to Rockport and had the interior completely gutted and replaced, including new overheads, bulkhead paint, new heads, flooring, upholstery and interior varnish, along with new wiring and plumbing runs. Once the remake was completed, the boat’s owner ran her for three seasons in Maine, then put her on the market.

Enter Sam Rowse and Martha Coolidge, accomplished sailors who race competitively and whose 1932 Sparkman & Stephens-designed Six Meter was restored a few years earlier by Rockport (Maine) Marine. The couple also owns a 1971 wooden 58-foot Trumpy that’s undergoing a major refit at Yachting Solutions, with an all-new bottom – keel, ribs and planking.

The common thread here is quality wooden boats that are worth giving a new lease on life. Consider that a well-built wooden boat can easily last 50 years with proper care, and can then be rebuilt to last another 50 years. With that in mind, the rationale for a person who loves the soul, quirks and individuality of a well-drawn, intelligently designed and well-built wooden boat becomes clear.

Rowse and Coolidge had seen the Huckins during the last few seasons in the Rockport area, where they have a home, and liked the lines and the way she went through the water. When Rowse saw the boat out behind Yachting Solutions’ storage building, he asked Morong about it. Morong told him that the owner had just put it up for sale and within a few days Rowse had an agreement to purchase the Huckins.

PROJECT SUITABILITY

While the yacht was in good basic shape structurally and cosmetically, the propulsion system was another matter. She had a pair of vintage Cummins 4-cylinder diesels with V-drive transmissions and shafts at a very steep 16-degree angle. The engines were inherently unbalanced, so they rattled and shook to beat the band, especially at low speeds.

That was OK, because Rowse was excited about Volvo Penta pod power and, in fact, bought the Huckins with Volvo’s IPS in mind. What he really liked about IPS was the ability to gain efficiency through technology, and this translates into greater range. He also wanted family members to be able to run the boat and Volvo’s joystick control makes it possible for an amateur to handle an IPS-powered 60-footer after just a few hours at the helm.

In my own testing, I’ve found IPS to be the most efficient pod system on the market. Also, it does not require propeller pockets, so installation in an existing boat is considerably simplified for the builder. And without pockets, there is no corresponding loss of buoyancy and dynamic lift, which is a big help since these boats tend to run bow-high if left to their own devices.

Rowse contacted Paul Waring, of Stephens, Waring and White Yacht Design (www.swwyachtdesign.com) in Brooklin, Maine, to start reviewing the boat plans for IPS suitability. They also looked at Zeus and ZF pod drives. Waring, who had done design work for Rowse and Coolidge on previous projects and had built a 56-foot cold-molded Sparkman & Stephens sloop through his firm’s affiliate Brooklin Boat Yard, did a feasibility study.

In the end, everyone on the team had the most confidence in IPS, both the drive itself and the engineering support for boatbuilders. “Volvo really has their engineering together,” says Morong. “They provide real-time engineering data, real-time speed and trim projections. Their in-house engineering is very well organized and we felt confident that this would be a successful project with Volvo’s expertise behind us.”

And ordering an IPS system is greatly simplified. Volvo is the only vendor and one part number covers the whole system, with all parts and costs documented in detail. Volvo also offers engine-room design services, including auxiliary equipment layout and wiring and plumbing runs. This soup-to-nuts service is good business for Volvo, as it eliminates much of the opportunity for IPS failure that might otherwise exist, and it makes builders much more comfortable with the process and, therefore, more willing to shift over to the IPS system in the first place.

Although the Huckins repower team was sold on IPS, Volvo had to be sold on the Huckins. A few years ago, Volvo opened an 18,500-square-foot Boat and Engine Integration Center on the Intracoastal Waterway in Chesapeake, Va. The BEIC staff includes engineers and fiberglass experts who manage IPS installations in custom yachts and in the first hull of a series to be produced by a builder.

While a new boat is still in the design phase, Volvo gets a copy of the plans and reviews them for compatibility with IPS. The shape of the bottom, appendages such as keels and strakes, the longitudinal center of gravity, the boat’s displacement and the location of its fuel and water tanks are all scrutinized, and modifications are made while it’s still easy to do so. After IPS is installed in the first hull or prototype of a series, techs rig a temporary helm and run the boat, verifying performance data before shipping it back to the builder.

Volvo BEIC general manager Ed Szilagyi made the trip to Maine to inspect the Huckins and make sure IPS would work in her wooden hull. Not only did the hull design and condition have to be a fit, but Szilagyi wanted to be confident that the yard had the technical competence and skills to integrate the wood hull and the fiberglass pod structure so there would be no weak links. The boat and the Yachting Solutions team passed muster and it was on to the next phase.

“Yachting Solutions was already a Volvo repair facility and we had made a commitment to IPS training with our Lazzara Yachts affiliation, so it was a natural fit from that perspective as well,” says Morong.

Pod power creates altogether different loads on the hull than a conventional inclined-shaft inboard drive. The IPS engines sit on beds, usually part of and continuous with the hull’s stringer system, but the mounts don’t have to absorb the propeller thrust, just the weight of the engines. This allows them to float more freely, reducing structure-borne vibrations felt by passengers.

The diesels are connected to the pods with short jackshafts that transmit the engine’s power. The pods themselves are mounted directly to collars built into the hull. This support structure is critical, since they have to be able to withstand not only the thousands of pounds of thrust (and lever arm) developed by the propellers, but also must be able to absorb the shock of running aground at high speed and even tearing the pods off the hull. The pods are designed to shear off and leave a watertight seal behind – a better guarantee than you get with a regular inboard – so the importance of getting this right is pretty clear.

For this reason, the support structure for the engines and pods is specified by Volvo in exacting detail, including its precise lamination schedule. Nothing is left to chance or the boatbuilder’s whim or creativity. In the case of existing boats, Volvo either blesses the design as is or requires modifications. The Huckins hull form, appendages and center of gravity were OK as they were, which simplified the process.

Installing IPS in a hull originally designed for straight shafts can be more complicated than it may appear. First, IPS’s horizontal thrust angle tends to raise the bow, especially when coming up on plane, so bottom modifications or weight shifts may be needed to compensate. IPS also weighs substantially less than conventional inboards and the system’s center of gravity is typically farther aft. And then there’s the issue of what to do with all the extra space gained by the IPS’s compact size. All of these factors must be taken into account.

PREPPING THE HULL

During a two-day visit to Yachting Solutions, I was invited to sit in on a planning meeting with Rowse, Morong, designer Waring and master craftsman Brad Ellsworth, who is responsible for rebuilding the hull around the engine room and installing the drives. The conversation and debate was very much to the point because it revolved around the extent to which the Huckins was to become a fiberglass boat back aft to support the propulsion system loads.

One option discussed was to fiberglass the inside of the hull sides from the chine up to the sheer. This was nixed for two reasons. First, the wooden hull-side structure, already sheathed on the outside in fiberglass, was deemed strong enough to support the loads, in large part due to the inherent strength of the diagonal planking, which distributes and attenuates stresses effectively.

Second, when you sheath wood on both sides, you can’t see what’s happening to it, and the wood can’t breathe, which invites trouble. If water were allowed through tiny cracks in the bottom over time, you basically would have oatmeal mush for planking in 10 years. And you wouldn’t know it until you came down to the boat some morning to find it sitting on the bottom, though a surveyor could find it with the right moisture-sensing tools.

There’s another, simple reason for not going crazy with the glass: The owner wants to retain as much of the original structure as is practical.

One trick with this job is to distribute the pod propulsion loads to the hull not only locally but also globally, in a macro sense. If you simply stop a thick fiberglass laminate at a certain spot in the hull, the edge or perimeter of the glass creates hard spots or stress points in the surrounding wood structure. So the strategy involves following Volvo’s laminate schedule, which tapers the epoxy-saturated fiberglass gradually from the pod collars out to the chines and then 12 inches up the hull sides to a new longitudinal stringer that will run from the transom to the engine room bulkhead on each side of the boat.

New ribs will be installed from this stringer on each side up to the sheer clamp and these ribs and the diagonal hull-side planking will distribute the loads to the deck. The bulkhead will also be stiffened by a new ring frame around its perimeter.

During the discussion, glassing up to the sheer on the inside of the hull was being debated, since this would have been an easy way to rebond some of the frames to the planking. This was being considered because the alternative was refastening the planking to the frames from the outside, which would have meant an expensive paint job on a hull that did not need repainting. However, Rowse felt the right approach was to replace the framing (with slightly larger ribs to make them easier to fasten to) and fasten them from the outside of the hull, readily accepting the new paint job.

The forward engine-room bulkhead is about 9 feet forward of the transom. Rather than rebuild the hull bottom to this point, Waring and the team opted to continue forward 3 more feet, tying in to the original planking with the new wood being supported by more of the hull’s framing forward in the hull. While the original mahogany bottom planking was solid, it was diesel- and lube oil-soaked from years of use, so the epoxy resin’s bond would have been tenuous, at best.

The inner and outer chine logs to starboard and the outer chine log to port will also be replaced, as will the bottom third of the transom, which had gotten a little punky through the years. The outside of the hull bottom will be resheathed with fiberglass set in epoxy resin.

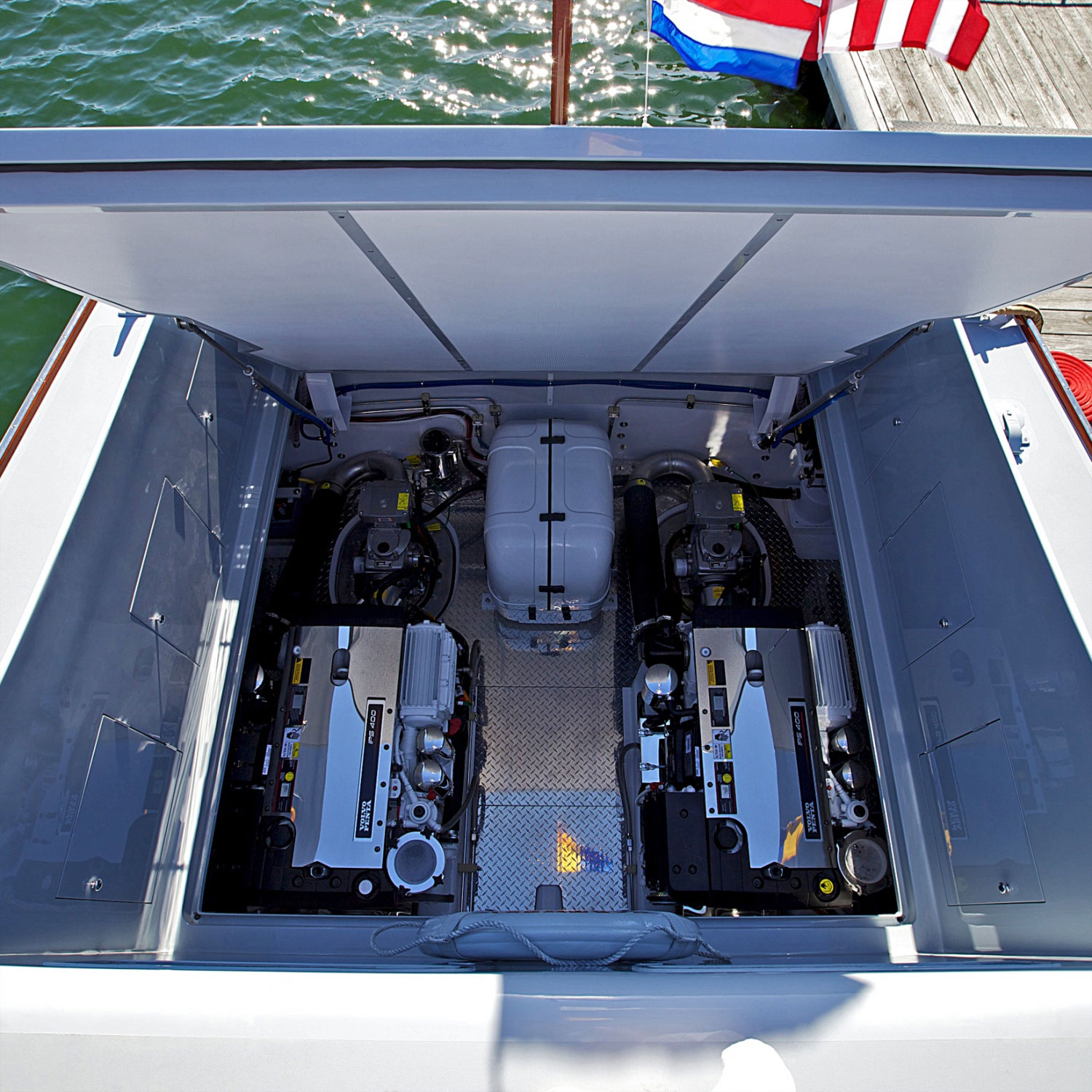

The 300-hp Volvo IPS 400 D4 diesels sit a little higher than the Cummins diesels, so the aft deck is being raised 4 inches. This boat has a great deal of freeboard that continues all the way to the stern, which serves to strengthen and stiffen the hull. The raised deck is going to have a one-piece hatch, hinged at the aft end, that will open to the engine room for access. A deep gutter with large drain lines and a flange around the edge of the hatch will keep things dry down below. An 8-kW generator will sit between the Volvos. That’s a small genset for a 21st century 45-footer, but just right for this more practical 1954 model.

THE SEQUEL

I’m going to follow up on this project after the boat is launched in the spring. The Huckins had a 16-knot cruise and 21-knot top speed with the Cummins V-drives. With the Volvo IPS setup, a cruise of 25 knots and top end of 30 knots is expected. We’ll look at before-and-after performance charts showing speed, fuel flow and nautical miles per gallon, and also take a walk through the boat.

One thing that makes this boat so well-suited to IPS power is that it already has an aft engine room, which is where an IPS setup goes. The inherent beauty of this 56-year-old cruiser, and a primary reason for its suitability for an IPS repower, is that the machinery is isolated acoustically and vibration-wise from the accommodations. Riding in the main saloon or forward cabin in this boat has got to be whisper quiet as a result.

This Huckins, designed before boats lugged along granite countertops and washer/dryers, is meant to be cruised on, but in a much different way than we see today aboard your typical condo-esque creation.

STAY TUNED …

Eric Sorensen was founding director of the J.D. Power and Associates marine practice and is the author of “Sorensen’s Guide to Powerboats: How to Evaluate Design, Construction and Performance.” A longtime licensed captain, he can be reached at [email protected].

FOLLOW UP

Sam Rowse’s 45-foot Huckins now sports Volvo Penta IPS pod propulsion, courtesy of Yachting Solutions.

Our last trip down memory lane took place aboard Northern Spy, Sam Rowse’s 1954 45-foot Huckins that he had stripped down to parade rest, lovingly restored to better-than-ever condition and repowered with Volvo Penta IPS pod propulsion. What a great combination. The boat now has a whole new bottom, and she’s stronger than ever with epoxy and fiberglass sheathing and a heavily laminated bottom around the engine room built to Volvo’s specs, tying the hull together into a single unit.

The boat originally had a pair of Cummins V-drives in her, but they’d gotten tired over the years and were shakers as well as movers. Sam wanted a boat that his kids could run easily, and a cruise speed in the mid-20-knot range – an 8-knot improvement – was just the ticket.

Like most rebuilding projects, whether it’s a house or a boat, this one was a lot more extensive than Sam had counted on, but the end result was a delightful cruiser that handles like a baby carriage. A child could dock the boat in a stiff crosswind after an hour of tutelage at most.

I’d seen the Huckins in its snow-covered shed last winter, where Bill Morong’s Yachting Solutions crew in Rockport had torn her apart, and all the king’s men were getting ready to put her together again. When I saw her down at the dock in October, she’d been in the water for a month and was hot to trot and back in operation. The boat was Awlgripped from top to bottom in a beautiful shade of haze gray that makes you wonder why every boat isn’t painted the same color, and she was looking just peachy, ready for a gallop around the bay.

The proportions on this 57-year-old Huckins are just right, too. The deckhouse is small, and the hull is big, just the way it should be, not the other way around, as is the case with 70 percent of the boats being produced today. The interior is flooded with sunlight through all those big windows, and the master stateroom aft and guest stateroom forward are separated by the pilothouse, or saloon if you must, lending a degree of privacy, simplicity and comfort not seen on many boats built today.

We had maybe a 1-foot chop on Penobscot Bay, so the sea conditions didn’t challenge the boat. The twin 300-hp Volvo D4 diesels driving IPS pods through short jackshafts pushed the Huckins to 28 knots at 3,500 rpm, and she did an easy 22 knots at 3,000 rpm, burning 21 gph, which translates to slightly more than 1 nautical mile a gallon. If you’re not up on this kind of thing, that’s really good for a 26,000-pound boat, 20 to 30 percent better than many similar size boats today.

THE HUCKINS 45 RETAINS THE ELEGANCE OF HER 57-YEAR-OLD PEDIGREE.

The boat handled nimbly, with just 3.5 turns lock to lock, though it also turned flatter than other IPS boats I’ve run, a result of the boat’s shallow keel resisting transverse slip in a turn and the hull’s flat sections aft, which orient the pods at a correspondingly vertical angle. On a planing boat with 20 degrees of deadrise, which is more the norm for an IPS installation, the pods are 20 degrees from vertical, normal to the hull bottom, and thrust oriented at this angle makes the boat heel more in a turn. When centrifugal force goes right down through your feet or seat, as it does in a banking airplane, rather than throwing you off to the side, it makes for a safer boat. This angle, which Volvo calls a true turn, is more nearly achieved by a boat with 15 or 20 degrees of deadrise. The Huckins’ flatter turn is the only fault I could find with this IPS installation, not that I came in looking for it. But because this diagonal-planked mahogany boat needs a healthy blocking keel to keep her back straight, I’ll just deal with it.

This is one quiet boat, inside and out. Even at 3,000 rpm in the master stateroom, just forward of the engine room, I measured only 79 dBA. In the wheelhouse, it was just 75 dBA, which is as quiet as it gets on any Alden or Riviera, the two quietest diesel-powered boats I’ve been on.

As with any IPS boat, the joystick control takes all the fun out of boat handling. That is to say, there is no challenge whatsoever in docking it. Driving this boat competently after some perfunctory instruction is akin to being able to play a Scriabin etude on the piano competently after 20 minutes of practice. (Someone needs to make a joystick for the piano!)

This 1950s-era Huckins (www.huckinsyacht.com) has many features that contemporary boatbuilders trumpet as new discoveries – marvels, really, in their own boats – such as a full-beam master stateroom, cabins flooded with light from big windows, great engine room access (although nothing out there even approaches this boat in the latter two categories) and, of course, pod power.

Hats off to Sam for his vision and resolve, and to Bill and his crew for pulling off the rebuild, which was an unqualified success. This beauty is a first cousin of the World War II PT boat, and like recharging a battery, she has at least that many more years built back into her, given reasonable care at Yachting Solutions, according to Bill.